PART 8 | The Earliest Biography of Bodhidharma: A Translation from the Xu Gaoseng Zhuan

The Biography of Bodhidharma in the Xu Gaoseng Zhuan (續高僧傳), Scroll 16

Why This Text Matters

The biography of Bodhidharma preserved in the Xu Gaoseng Zhuan (續高僧傳, Further Biographies of Eminent Monks) is among the earliest surviving Chinese accounts of the figure who would later be remembered as the First Patriarch of Zen. Unlike the richly elaborated Bodhidharma legends found in later Chan literature—accounts of wall-gazing, reed-crossing, encounters with Emperor Wu, or dramatic gestures of transmission—this record is brief, restrained, and historically revealing.

Its importance lies precisely in its early perspective. Bodhidharma appears here before Zen had fully defined itself, and before his image was shaped by later sectarian concerns. In this text, he is not yet presented as a singular founder or iconic patriarch, but as a foreign practitioner of dhyāna (禪) situated within an already existing Chinese Buddhist world. Reading this biography carefully allows us to glimpse how Bodhidharma was understood in the mid-seventh century, rather than how he would later be remembered.

The Xu Gaoseng Zhuan: Historical Context and Purpose

The Xu Gaoseng Zhuan was compiled in the mid-Tang dynasty by Daoxuan (道宣, 596–667), one of the most influential Vinaya masters and Buddhist historians of early medieval China. The work was completed around 645 CE as a continuation of earlier biographical collections, most notably Huijiao’s Gaoseng Zhuan (高僧傳).¹

Daoxuan did not write biography in the modern historical sense. His aim was not neutral reconstruction, but the preservation and moral presentation of exemplary monastic lives. Figures are grouped according to functional categories—Vinaya specialists, translators, miracle workers, and practitioners of dhyāna—reflecting what Daoxuan understood to be the functional structure of the Buddhist community.²

As a historical source, the Xu Gaoseng Zhuan is therefore both indispensable and uneven. It preserves early traditions, reputations, and lineages that would otherwise be lost, while simultaneously shaping those materials through hagiographic conventions, institutional priorities, and rhetorical ideals. Its greatest value lies not in isolated factual claims, but in the patterns of memory and authority it records.³

Bodhidharma’s Placement in Scroll 16

Bodhidharma appears in Scroll 16, within the section titled 習禪初, best rendered as Early Practice of Dhyāna. This placement is crucial for understanding how Daoxuan framed him. Bodhidharma is not introduced as a sectarian founder, nor as the originator of dhyāna in China, but as one figure among a group of early dhyāna practitioners.

Within this section, Bodhidharma’s biography is the fifth entry. Four practitioners precede him:

Sengfu (僧副), a Liang-dynasty Chinese monk associated with Dinglin Monastery

Huisheng (慧勝), also known as Huichu (慧初), another Liang-dynasty dhyāna practitioner

Daozhen (道珍), active in the Mount Lu (廬山) region and associated with disciplined practice

Fotuo (佛陀), an Indian monk connected with the Mount Song / Shaolin area

None of these figures are presented as Bodhidharma’s teachers, disciples, or lineage ancestors, nor are they described as members of anything resembling “Zen” in the later sense. Their presence instead demonstrates that dhyāna practice was already established in China, among both Chinese and foreign monks, prior to Bodhidharma’s arrival.⁴

This ordering directly challenges later narratives that portray Bodhidharma as introducing dhyāna to China. In Daoxuan’s account, he is part of an existing current, not its point of origin.

Figures Directly Connected to Bodhidharma in the Text

Within the Xu Gaoseng Zhuan itself, only one figure is explicitly linked to Bodhidharma: Huike (慧可), whose biography immediately follows Bodhidharma’s in Scroll 16.

Huike is presented as Bodhidharma’s principal disciple, and his biography contains the only retrospective framing of Bodhidharma found elsewhere in the work. Significantly, all references to Bodhidharma in the Xu Gaoseng Zhuan occur within these two adjacent biographies. There are no later anecdotes, no scattered references in other scrolls, and no expanded legend cycle.⁵

菩提達摩傳

The Biography of Bodhidharma

原文

菩提達摩。南天竺婆羅門種。

譯文

Bodhidharma.

Of the brahmin lineage of South India.

原文

神慧疏朗,聞皆曉悟。

譯文

His numinous wisdom was open and clear;

what he heard, he fully understood.

原文

志存大乘,冥心虛寂。

譯文

His resolve abided in the Mahāyāna;

his mind was darkly merged in emptiness and quiescence.

原文

窮微徹數,禪眾高之。

譯文

He exhausted subtlety and penetrated underlying patterns;

the community of dhyāna practitioners esteemed him highly.

原文

悲此邊隅,以法相導。

譯文

Moved with compassion for these frontier regions,

he guided them by means of the Dharma.

原文

初達宋境,南越為先。

譯文

He first reached the territory of Song,

with the southern Yue as his initial destination.

原文

末又北度,至於魏邦。

譯文

In the end he again crossed north,

arriving in the land of Wei.

原文

隨所止處,誨以禪教。

譯文

Wherever he stopped,

he instructed through the dhyāna tradition.

原文

于時名僧,盛弘講肆。

譯文

At that time renowned monks

were vigorously promoting lecture halls.

原文

乍聞禪法,多生譏謗。

譯文

Upon first hearing the dhyāna teaching,

many gave rise to ridicule and slander.

原文

有道育慧可二沙門。

譯文

There were two śramaṇas⁶,

Daoyu and Huike.

原文

雖在後學,銳志高遠。

譯文

Though later students,

their keen resolve was lofty and far-reaching.

原文

初逢說法,知有所歸。

譯文

Upon first encountering his teaching,

they knew there was somewhere to return.

原文

親事積年,給侍咨承。

譯文

They personally attended him for many years,

providing service and receiving instruction.

原文

感其精誠,誨以真法。

譯文

Moved by their sincerity,

he instructed them in the true Dharma.

原文

如是安心,謂之壁觀。

譯文

Thus settling the mind—

this is called wall-contemplation.

原文

如是發行,謂之四行。

譯文

Thus arousing practice—

this is called the Four Practices.

原文

如是順物,教護譏嫌。

譯文

Thus according with circumstances,

he taught guarding against slander and reproach.

原文

如是方便,教令不著。

譯文

Thus by skillful means,

he taught causing non-attachment.

原文

然則入道多途,要唯二種。

譯文

Thus, entry into the Way has many paths,

but the essentials are only two kinds.

原文

謂理行也。

譯文

They are called entrance through Dharma-nature

and entrance through practice.

原文

藉教悟宗,深信含生同一真性。

譯文

Relying on teachings to awaken to the source,

deeply trusting that all sentient beings share one true nature.

原文

客塵障故,令捨偽歸真。

譯文

Because it is obscured by guest-dust,

one turns away from the false and returns to the true.

原文

凝住壁觀。

譯文

Settling and abiding in wall-contemplation.

原文

無自無他,凡聖一等。

譯文

No self, no other;

ordinary and sage are equal.

原文

堅住不移,不隨他教。

譯文

Firmly abiding without movement,

not following other teachings.

原文

與道冥符,寂然無為。

譯文

Darkly tallying with the Way,

quiescent and non-active.

原文

名理入也。

譯文

This is called entrance through Dharma-nature.

菩提達摩傳(四行)

The Four Practices

原文

行入四行,萬行同攝。

譯文

Entrance through practice is four practices;

the myriad practices are all encompassed within them.

一曰報怨行

The First Practice: Accepting Karmic Conditions

原文

修道行人,受苦至時,當念往劫。

譯文

When a practitioner cultivating the Way encounters suffering,

he should recollect past kalpas (immensely long period of time, far beyond a single lifetime).

原文

捨本逐末,多起愛憎。

譯文

Abandoning the root and pursuing the branches,

many loves and hatreds arose.

原文

今雖無犯,是我宿作。

譯文

Although there is no offense now,

this is what I formerly created.

原文

甘心受之,無怨無訴。

譯文

Willingly accept it,

with no resentment and no complaint.

原文

經云:「逢苦不憂。」

譯文

The sūtra says:

“Meeting suffering, do not grieve.”

原文

識達故也。

譯文

This is because of understanding and penetration.

原文

此心生時,與道無違。

譯文

When this mind arises,

it does not oppose the Way.

原文

體怨進道故也。

譯文

This is because resentment is embodied

and the Way advanced.

二曰隨緣行

The Second Practice: Being in Accord with Conditions

原文

眾生無我,苦樂隨緣。

譯文

Sentient beings have no self;

suffering and joy follow conditions.

原文

縱得榮譽等事,

皆由宿因,今方得之。

譯文

Even if one attains honor, praise, and similar matters,

all are due to former causes,

now only obtaining them.

原文

緣盡還無,何喜之有。

譯文

When conditions are exhausted, they return to nothing—

what joy is there?

原文

得失隨緣,心無增減。

譯文

Gain and loss follow conditions;

the mind neither increases nor decreases.

原文

違順俱忘,冥順於道。

譯文

Opposition and compliance are both forgotten,

darkly conforming to the Way.

三曰無所求行

The Third Practice: Non-Seeking

原文

世人長迷,處處貪著。

譯文

Worldly people are long deluded,

everywhere grasping and clinging.

原文

名之為求。

譯文

This is called seeking.

原文

智者悟真,理與俗反。

譯文

The wise awaken to the true;

principle runs counter to the worldly.

原文

安心無為,形隨運轉。

譯文

Settle the mind in non-action;

the body follows the turning of conditions.

原文

三界皆苦,誰為安者。

譯文

The three realms are all suffering—

who could be at ease?

原文

經云:「有求皆苦。」

譯文

The sūtra says:

“All seeking is suffering.”

原文

無求乃樂。

譯文

Having no seeking is joy.

四曰稱法行

The Fourth Practice: Accord with the Dharma

原文

性淨之理,目之為法。

譯文

The principle of nature’s purity

is designated as the Dharma.

原文

此理眾相,皆無染著。

譯文

In this principle, the many appearances

are all without defilement or attachment.

原文

無我無人,無眾生無壽者。

譯文

No self, no person,

no sentient being, no life-span.

原文

經云:「法無眾生。」

譯文

The sūtra says:

“The Dharma has no sentient beings.”

原文

離垢故也。

譯文

This is because it is free from defilement.

原文

智者信解此理,

應行稱法。

譯文

The wise trust and understand this principle,

and should practice in accord with the Dharma.

原文

法體無慳,身命財行施。

譯文

The body of the Dharma has no stinginess;

with body, life, and wealth, one practices giving.

原文

心無吝惜。

譯文

The mind has no reluctance.

原文

離相離著,無染無取。

譯文

Free from marks, free from attachment,

without defilement and without grasping.

原文

隨順眾生,等施一切。

譯文

Following and complying with sentient beings,

giving equally to all.

原文

不住於相,名為施也。

譯文

Not abiding in marks—

this is called giving.

原文

除去妄想,修行六度。

譯文

Removing false thoughts,

one cultivates the six pāramitās.⁷

原文

而實無所行。

譯文

Yet in truth,

there is nothing practiced.

原文

是名稱法行。

譯文

This is called

the practice of accord with the Dharma.

菩提達摩傳(終)

Conclusion

原文

達摩禪師,隨其所止,誨以禪宗。

譯文

Dhyāna Master Bodhidharma,

wherever he resided,

instructed by means of the dhyāna tradition.

原文

門徒雖眾,得法者寡。

譯文

Although his disciples were many,

those who obtained the Dharma were few.

原文

唯可一人,密承心印。

譯文

Only Huike alone

secretly received the mind-seal.

原文

付法之後,默然西返。

譯文

After transmitting the Dharma,

he silently returned west.

原文

或云至葱嶺。

譯文

Some say he reached the Onion Range.

原文

或言沒於熊耳。

譯文

Others say he passed away

at Bear’s Ear Mountain.

原文

未詳其終。

譯文

His end is not clearly known.

原文

後魏使者宋雲,西域還,

見達摩於葱嶺,唯履一隻。

譯文

Later, the Northern Wei envoy Song Yun

returned from the Western Regions

and saw Bodhidharma at the Onion Range,

wearing only a single sandal.

原文

問之,云:「西還。」

譯文

When asked, he said:

“Returning west.”

原文

及還,具以告朝。

譯文

Upon returning,

he reported this fully to the court.

原文

朝廷怪之。

譯文

The court regarded it as strange.

原文

後啟塚,唯得一履。

譯文

Later, when the tomb was opened,

only a single sandal was found.

Conclusion: Seeing Bodhidharma Before Zen

The portrait of Bodhidharma preserved in the Xu Gaoseng Zhuan is striking precisely because of its restraint. Here, Bodhidharma appears not as a fully formed Zen patriarch or the founder of a new school, but as a dhyāna practitioner situated within an existing Buddhist community, transmitting a way of practice already intelligible in his time.

The framework of two entrances and four practices is presented not as abstract philosophy, but as a lived path—one concerned with endurance, responsiveness to conditions, non-seeking, and accord with the Dharma. These teachings are grounded in ordinary human experience: suffering, reputation, effort, loss, and relationship. They do not rely on dramatic awakening stories or later lineage mythmaking. The emphasis is on how one lives and practices, moment by moment.

Reading this text alongside later Chan sources makes clear how much Bodhidharma’s image would expand and harden over time. This earlier account reminds us that Zen did not begin as an icon, a slogan, or a set of paradoxes. It began as practice—quiet, demanding, and ethical—embedded in a historical world that had not yet decided what Zen would become.

Why This Matters for Modern Zen Practice

Seen through this early record, Zen practice appears less as a dramatic breakthrough and more as a discipline of steady alignment. The four practices do not promise transcendence of daily life. They ask for full participation in it—meeting suffering directly, responding to conditions wisely, and letting go of the need to secure certainty or outcome.

For modern practitioners, this can serve as a gentle corrective. Zen need not be fast, clever, or performative. It need not depend on paradox or display. It can look like showing up consistently, responding honestly to what arises, and allowing practice to mature over time.

Read this way, Bodhidharma is not primarily a symbol or a legend. He is a reminder that Zen begins—and continues—in the simplest place: how we meet this moment, without turning away.

Endnotes

Daoxuan 道宣, Xu Gaoseng Zhuan 續高僧傳 (Further Biographies of Eminent Monks), ca. 645 CE. Taishō Tripiṭaka, T2060.

John Kieschnick, The Eminent Monk: Buddhist Ideals in Medieval Chinese Hagiography (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1997).

Jan Nattier, “Biographical Sources in Chinese Buddhist History,” in Chinese Buddhist Biography, ed. Phyllis Granoff and Koichi Shinohara (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1994).

Daoxuan, Xu Gaoseng Zhuan, T2060, Scroll 16, 習禪初 section.

Ibid., Scroll 16, 菩提達摩傳 and 慧可傳.

A kalpa (Skt.) denotes an immensely long cosmological period, used to express karmic continuity across lifetimes rather than a measurable span of time.

The six pāramitās (generosity, ethical conduct, patience, effort, meditative stability, and wisdom) are cultivated here without attachment to practice or attainment.

Brief Translation Notes

Dhyāna (禪) is left untranslated throughout to preserve its early, pre-Chan meaning and to avoid importing later sectarian connotations.

Wall-contemplation (壁觀). In an earlier post, I rendered 壁觀 as wall-gazing, with an explanation that the term refers to contemplation rather than the physical act of staring at a wall. In this translation, 壁觀 is rendered more precisely as wall-contemplation. The character 觀 (guan) denotes contemplation or discernment, not visual gazing (which would typically be expressed with characters such as 視 or 看). While wall-gazing is familiar from later Chan literature, it reflects a later interpretive gloss rather than the wording of the Xu Gaoseng Zhuan itself.

Entrance through Dharma-nature / entrance through practice is aligned with the terminology used in the Erru Sixing Lun to reflect a shared doctrinal framework, while preserving the compressed biographical presentation of the Xu Gaoseng Zhuan. For a detailed discussion, see my earlier post on the Two Entrances and Four Practices.

For a deep dive into the Two Entrances and Four Practices, check out my earlier blog on the Erru Sixing Lun:

https://www.mindlightway.org/zen-history-blog/two-entrance-four-practicesMiraculous elements (such as the single sandal) are translated plainly, without endorsement or reinterpretation, consistent with the conventions of Buddhist biographical literature.

Note on the Source Text and Edition Used

This translation is based on the CBETA online edition of the Xu Gaoseng Zhuan, specifically:

Taishō Tripiṭaka, T2060, Scroll 16

Xu Gaoseng Zhuan (續高僧傳), compiled by Daoxuan (道宣, 596–667)

CBETA reference: T2060_016

https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/zh/T2060_016

CBETA’s Taishō-based digital text was selected for its scholarly reliability, standardized lineation, and ease of cross-referencing with modern academic research. Line divisions, punctuation, and orthographic conventions follow the Taishō canon as represented in CBETA.

Punctuation has been interpreted conservatively, and no emendations have been made unless explicitly indicated. The translation aims to remain close to the original wording and structure of the Chinese text while preserving its non-sectarian, pre-Chan framing. Later Chan sources and variant traditions are not used to retroactively clarify or harmonize the account presented here.

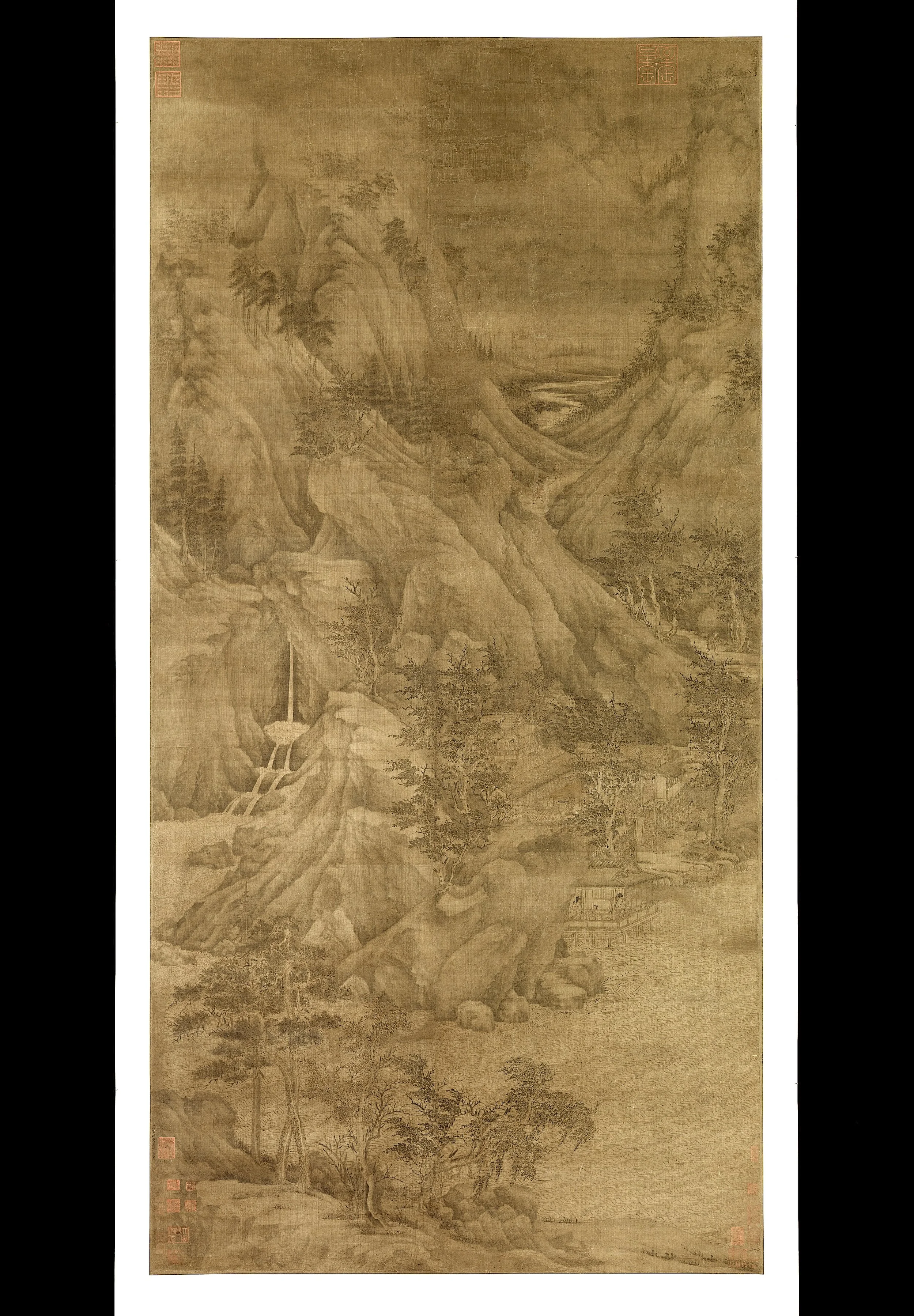

Attributed to Dong Yuan (active 10th century), Riverbank, ink on silk.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Public domain.