PART 7 | Zen-Chán-Dhyāna

What Did Early Chán (Zen) Masters Mean by “Chán/禪”?

When people ask what the word Zen means, they usually get a dictionary answer: meditation. But that definition flattens what early Chán masters actually meant by 禪. This post traces the word by following the sources they pointed to—and then unpacking how they defined it.

In modern times, the word “meditation” can mean so many different things—from mindfulness apps to relaxation techniques—that its meaning has become blurred. This raises a question: how did the original Zen and Buddhist sources define chán (禪)? What did early Zen masters actually mean when they used this word?

The English word Zen (禅) comes from the Japanese Zen, which comes from the Chinese Chán (禪), itself derived from the Sanskrit dhyāna (ध्यान) and Pali jhāna. The term dhyāna was first transliterated into Chinese as chánnà (禪那) and later shortened to chán (禪).¹

Often in English, Zen, Chán, and dhyāna are translated simply as “meditation.” Sometimes it’s assumed to be shorthand for zazen (坐禪, sitting meditation). But early Chán masters drew clear distinctions: chán (禪) was not identical with zuòchán (坐禪, sitting chán).

This article presents each key passage with (1) the original Chinese text, (2) a literal translation faithful to the Taishō edition, (3) key terms explained, (4) a contemporary rendering in plain English, and (5) commentary to situate it in context. Footnotes rely on primary sources (Taishō/CBETA) and minimal reference works.

1. The door Mazu opens

According to Mazu Daoyi, Bodhidharma “came from South India, transmitted the One-Mind teaching, and cited the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra to seal the mind-ground of sentient beings.”² This short statement gives us a clear route: if we want to know what early Chán meant by 禪, we should start where the lineage itself points—to the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra.

Mazu (709–788) was one of the most influential Tang dynasty Chán masters, remembered for shaping the style and methods that came to define much of later Zen. His words carry special authority: they frame Bodhidharma’s mission, and they highlight the very scripture the Chán lineage upheld as its seal—the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra. Later records, such as the Jingde chuandeng lu (景德傳燈錄, Record of the Transmission of the Lamp, compiled 1004 CE), even present Mazu as the founding figure of the Hongzhou school—the branch of Chán that became the dominant style of the Tang and the source of many Zen teachings that spread to later generations.³

2. Brief historical context: the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra

The Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra is a Mahāyāna scripture set in Laṅkā (Sri Lanka) and framed as a dialogue between the Buddha and the bodhisattva Mahāmati. It deeply shaped early Chán thought. It survives in several Chinese translations, but for our purposes one is decisive:

– T670 (Laṅkāvatāra-avadāna-śāstra, translated by Guṇabhadra in the 5th century). This is the earliest surviving Chinese translation and the version most often cited by early Chán masters. It forms the basis of our discussion in this article.

T670 presents a fourfold account of dhyāna (禪), which became a touchstone for Chán masters.⁴

It is this fourfold scheme that is within the sūtra that Mazu points us to, and which we will now examine directly.

3. The Laṅkāvatāra’s four kinds of dhyāna (禪)

Chinese text (T670):

復次,大慧!有四種禪。何等為四?謂:愚夫所行禪,觀察義禪,攀緣真如禪,諸如來禪。

Literal translation (T670):

“Further, Mahāmati, there are four kinds of dhyāna. What are the four? Namely: the dhyāna practiced by the foolish; the dhyāna of examining the meaning; the dhyāna that takes hold of true Suchness; and the Tathāgatas’ dhyāna.”⁵

Key terms:

大慧 (Dàhuì) / Skt. Mahāmati / “Great Wisdom” — the bodhisattva interlocutor of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra. His name combines mahā (“great”) and mati (“thought, understanding”). Appears throughout as the Buddha’s addressee.⁶

禪 (chán) / Skt. dhyāna, Pali jhāna — a transliteration of the Sanskrit dhyāna. In earlier Chinese Buddhist texts such as the Chánxíng faxǐang jing (T605), it appears as: “rehearsing the contemplation of death is called ‘vigorous practice of chán’” (精進行禪).⁷

愚夫 (yúfū) — literally “foolish person.” In Buddhist texts, this refers to practitioners of limited understanding, attached to preliminary stages of realization. The English “foolish” is literal, but here it carries the sense of “ordinary, deluded” rather than an insult.

真如 (zhēnrú) / Skt. tathatā — “Suchness or Thusness”: experience just-as-it-is, prior to conceptualization, judgments, or a subject–object split.

如來 (rúlái) / Skt./Pali Tathāgata — “Thus-Come/Thus-Gone One,” a standard epithet for a fully awakened Buddha, one whose life and activity flow from Suchness.

Contemporary rendering:

“Great Wisdom, there are four ways of practicing dhyāna. Which four? First, the dhyāna of limited understanding; second, the dhyāna of examining the meaning; third, the dhyāna that takes Suchness as its basis; and fourth, the dhyāna of the awakened ones, the Tathāgatas.”

Commentary:

The term 禪 already appeared in earlier Chinese Buddhist texts such as the Chánxíng faxǐang jing (T605), which states: “rehearsing the contemplation of death is called ‘vigorous practice of chán’” (精進行禪).⁷ This shows that 禪 was first used as a technical term for contemplative exercises. Read in light of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, such practices align closely with what the sūtra later categorizes as “the dhyāna practiced by the foolish” (愚夫所行禪): preliminary but limited forms of meditation tied to analytical observation, rather than to non-conceptual Suchness. In the following subsections, we will see how the sūtra develops dhyāna beyond this starting point.⁵

3.1 愚夫所行禪 — “the dhyāna practiced by the foolish”

Chinese text (T670):

大慧!云何愚夫所行禪?謂聲聞緣覺諸修行者,知人無我,見自他身骨鎖相連,皆是無常苦不淨相。如是觀察堅著不捨,漸次增勝至無想滅定,是名愚夫所行禪。

Literal translation (T670):

“Mahāmati, what is the dhyāna practiced by the foolish? It is this: practitioners among the śrāvakas (聲聞, shēngwén) and pratyekabuddhas (緣覺, yuánjué), having understood the non-self of the person, see—in one’s own and others’ bodies—the bones and joints connected, all as marks of impermanence, suffering, and impurity. Observing thus, they attach firmly and do not release; step by step, increasing in attainment, they arrive at the ‘cessation-without-thought’ concentration (無想滅定). This is called ‘the dhyāna practiced by the foolish.’”⁵

Key terms:

聲聞 (shēngwén, Skt. śrāvaka) — “hearers,” disciples who advance by hearing and practicing the Buddha’s teaching.⁸

緣覺 (yuánjué, Skt. pratyekabuddha) — “solitary realizers” who awaken on their own and do not teach widely.⁹

無想滅定 (wúxiǎng mièdìng) — “cessation-without-thought,” a concentration state attained by suppressing mental activity.

Contemporary rendering:

Mahāmati, what is the dhyāna practiced by those of limited understanding? It is a (contemplation-led) approach undertaken by “hearers” (śrāvakas) and “solitary realizers” (pratyekabuddhas). They affirm the non-self of the person, then examine both their own and others’ bodies as temporary collections of parts (“bones and joints connected”), regarding the body as marked by impermanence, suffering, and impurity. They hold fast to this analytical recognition and, progressing step by step, arrive at “cessation-without-thought.”

Commentary:

This stage is characterized by an intellectual understanding that there is no such thing as a self. By analyzing and contemplating the body as a temporary collection of parts, practitioners recognize impermanence and the delusion that self-conceptualization creates. They cling to this understanding until they reach the limits of thought and stop thinking. The sūtra acknowledges this as valid training, but its wording (“attach firmly and do not release”) signals a limitation: because it remains tied to analytical observation rather than non-conceptual Suchness. In this way, it is a valid step on the path, but incomplete when contrasted with the Tathāgatas’ dhyāna that follows.⁵ ⁸ ⁹

3.2 觀察義禪 — “the dhyāna of examining the meaning”

Chinese text (T670):

云何觀察義禪?謂知自共相人無我已,亦離外道自他俱作,於法無我諸地相義,隨順觀察,是名觀察義禪。

Literal translation (T670):

“What is the dhyāna of examining the meaning? Having already understood the non-self of the person in terms of own-characteristics and shared-characteristics, and having set aside outsiders’ constructs of both self and other, one examines, in accord [with the teaching], the characteristics of the stages with respect to the non-self of dharmas. This is called ‘the dhyāna of examining the meaning.’”⁵

Key terms:

自相 (zìxiāng) / 共相 (gòngxiāng) — “own-characteristics” vs. “shared-characteristics,” scholastic categories for analyzing phenomena.

外道 (wàidào) — “outsiders,” non-Buddhist views.

法無我 (fǎ wú wǒ) — “non-self of dharmas,” often glossed as “no own-nature” (svabhāva).

諸地 (zhū dì) — “the stages” (bhūmi) of realization.

Contemporary rendering:

Mahāmati, what is the dhyāna of examining the meaning? It is when, after seeing there is no fixed person, and rejecting theories of self versus other, one continues to examine in accord with the teaching how the constituents of experience (dharmas) also lack any fixed inherent nature. Step by step, one works through the key characteristics of the stages of realization.

Commentary:

This dhyāna still relies on conceptual analysis, but it refines the scope: from analyzing persons to analyzing dharmas themselves. It represents progress beyond the first type, yet remains within the framework of examination rather than direct, non-conceptual Suchness.

3.3 攀緣真如禪 — “the dhyāna that takes hold of Suchness”

Chinese text (T670):

云何攀緣真如禪?謂若分別無我有二是虛妄念,若如實知彼念不起,是名攀緣真如禪。

Literal translation (T670):

“What is the dhyāna that takes hold of true Suchness? If one discriminates non-self as two (of persons and of dharmas), that is a delusive thought; if one knows this as-it-is and that thought does not arise, this is called the dhyāna that takes hold of true Suchness.”⁵

Key terms:

無我 (wú wǒ) — “non-self,” applied here to both persons and dharmas.

虛妄念 (xūwàng niàn) — “delusive thought,” the mental fabrication that results from dualistic discrimination.

如實知 (rúshí zhī) — “to know as-it-is,” a standard Mahāyāna phrase for direct, non-conceptual knowledge.

Contemporary rendering:

Mahāmati, what is the dhyāna that takes hold of Suchness? It is when a person no longer divides “non-self” into two (persons versus dharmas). To make such a division is delusive thought. When one knows this directly, as-it-is, and that thought does not arise, that is the dhyāna that takes hold of Suchness.

Commentary:

This marks the shift from conceptual analysis to direct recognition. Dividing “non-self” into categories is identified as delusive thought; letting this division drop, one abides in Suchness as-it-is. Here dhyāna becomes non-conceptual, rooted in direct awareness.

3.4 諸如來禪 — “the dhyāna of the Tathāgatas”

Chinese text (T670):

云何諸如來禪?謂入佛地,住自證聖智三種樂,為諸眾生作不思議事,是名諸如來禪。

Literal translation (T670):

“What is the dhyāna of all the Tathāgatas? It is to enter the Buddha-ground; to abide in the three kinds of bliss of self-realized noble wisdom; and to perform inconceivable deeds for all sentient beings. This is called the dhyāna of the Tathāgatas.”⁵

Key terms:

佛地 (fódì) — “Buddha-ground,” the level of full awakening.

自證聖智 (zì zhèng shèng zhì) — “self-realized noble wisdom.”

三種樂 (sān zhǒng lè) — “three kinds of bliss”: (1) bliss of self-realized wisdom, (2) bliss of samādhi (the complete engagement with whatever arises, without clinging or rejection), (3) bliss of quiescent extinction.

不思議事 (bùsīyì shì) — “inconceivable deeds,” activity beyond conceptual grasp, performed for the benefit of beings.

Contemporary rendering:

Mahāmati, what is the dhyāna of the Tathāgatas? It is full realization of the Buddha-ground, abiding in the bliss of self-realized noble wisdom (in its three forms), and freely carrying out inconceivable activity for the sake of beings.

Commentary:

This stage portrays the dhyāna of the Tathāgatas as the unification of realization and compassionate activity that is lived out through liberating action, described as “inconceivable deeds” for the benefit of beings. The Buddha abides in the wisdom of direct insight, with complete engagement in whatever arises, and the joy and peace that are present without clinging or rejection—when craving, ignorance, and confusion are quieted.

4. Tracing the Path of Dhyāna and the Rise of Chán

Read as a whole, the four dhyānas trace a clear path. First comes analysis of the self and body until one recognizes that both are impermanent — contemplating this until thought itself runs out. Next is analyzing the meaning of this realization: after seeing there is no fixed person, rejecting theories of self versus other and examining how the constituents of experience also lack any permanent essence. The third stage is identifying the delusive nature of conceptual thoughts and dropping such divisions, living in direct awareness of experience as it is. Finally comes the culmination of the path: the wisdom of direct insight, the steadiness of samādhi (complete engagement with whatever arises, without clinging or rejection), and the joy and peace that are present when craving, ignorance, and confusion are quieted.

By the mid-Tang period, 禪 (Chán) was no longer only a practice-term but also the name of a distinct lineage: the Chán school (禪宗). The Lidai fabao ji (c. 774 CE) contains one of the earliest self-references, declaring: “Our Chán school is distinct from the other teachings” (我此禪宗,別於餘教).¹⁰ Later records, such as the Jingde chuandeng lu (1004 CE), further consolidated the identity of the school.¹¹ By this time, the title “Chán Master” (禪師) was also in common use, first appearing in Tang-era sources such as the Xu gaoseng zhuan, and later formalized when Empress Wu conferred it on Shenxiu as “Great Penetration Chán Master” (大通禪師).¹²

5. Huineng on Chán and Ding

Chinese text (Platform Sūtra, T2008):

外於一切善惡境界,心不動,名為『坐』;內見自性不動,名為『禪』。外離相為禪;內不亂為定。

Literal translation:

“Outwardly, when amid all good and bad conditions the mind is not disturbed, this is called ‘sitting.’ Inwardly, seeing one’s own nature unmoving, this is called ‘chán.’ Outwardly, to part from appearances is chán; inwardly, to be undisturbed is ding (samādhi).”¹³

Key terms:

– 六祖慧能 (Liùzǔ Huìnéng, Huineng) — the Sixth Patriarch of Chán (638–713 CE). Born in Xinzhou (modern Guangdong), Huineng was a seminal figure remembered for his emphasis on sudden awakening (頓悟, dùnwù). His words are preserved in the Platform Sūtra of the Sixth Patriarch (六祖壇經), the only Chán text classified as a sūtra.

– 定 (ding) / Skt. samādhi — the complete engagement with whatever arises, without clinging or rejection. In Huineng’s usage, it emphasizes the inseparability of samādhi and prajñā (wisdom).14

– 自性 (zìxìng) — “one’s own nature,” the fundamental clarity of mind.

Commentary:

Huineng reframes 禪 (chán) not as a posture, but as a quality of mind. “Sitting” is not simply a physical act but the capacity to remain unmoved amid favorable or unfavorable conditions. To see one’s own nature as steady is chán; to rest in this steadiness without confusion is ding, or samādhi. By pairing these together, Huineng shows that stability (samādhi) and clarity (prajñā) are “not two” — different names for one undivided realization. This teaching helped shape later Chán by redefining meditation not as merely a technique, but as the natural activity of an undisturbed mind.

6. A Living Definition of Chán (Zen) Today

If we gather together the threads of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, Mazu’s framing, and Huineng’s teaching, a living definition of 禪 (chán/dhyāna) emerges. Chán is not simply “meditation,” nor only the act of sitting in stillness.

Zen is a living practice that is inseparable from insight and wisdom. The path begins with contemplation that reaches beyond thought, moving past the split between subject, object, self, and experience. It leads to direct insight and experiential wisdom through seamless engagement with whatever arises, embodying the joy and peace that are present when craving, ignorance, and confusion are quieted. Ultimately, it blossoms as the liberation and wholeness of oneself living through inconceivable, compassionate activity that benefits all beings.

To practice Chán is to let the mind settle in its own clarity, without chasing thoughts or clinging to appearances — recognizing that awareness itself is steady and open, even as the contents of experience change and reveal their impermanence.

This definition is not new — it is what early Chán masters pointed to. The Laṅkāvatāra mapped a path from analysis and conceptual insight, through the dropping of divisions, into the lived freedom of direct insight. Huineng taught that “sitting” is not about posture but about remaining unmoved in the midst of all conditions. Both show that Chán is less a technique than a way of living from clarity.

Why does this matter today? In an age of constant distraction and pressure, it is easy to lose contact with this steady, open engagement. Chán reminds us that freedom does not depend on circumstances but on how we meet them. To practice Chán is to live with awareness that is undisturbed by gain and loss, steady amid change, and naturally compassionate in action. It is the art of being fully present with whatever is here — not turning away, not clinging, simply awake.

Zen is not found in books or words, but in how we meet this very moment. To sit, to walk, to work, to speak — if the mind is clear and undivided, that is Zen.

Stay Connected

Thank you for reading. I hope this post offers insight and encouragement for your journey. If you’d like to suggest future topics, I’d love to hear from you:

📩 contact@mindlightway.org

If you find these history blogs valuable, consider supporting the Mind Light Way School of Zen, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Your support allows us to continue sharing Zen’s rich tradition with a wider audience.

🪷 This article was written by Sebastian Rizzon, Zen Master of the Mind Light Way School of Zen.

Footnotes

Robert E. Buswell Jr. and Donald S. Lopez Jr., eds., The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014), s.vv. “dhyāna,” “Chán,” “Zen.”

馬祖道一《馬祖道一禪師廣錄》, 收於《四家語錄》卷一:「……又引《楞伽經》,以印眾生心地……」。卍續藏 X 69, no. 1321, 1:2a24–b21 (CBETA), accessed September 20, 2025.

《景德傳燈錄》卷六(大中祥符年間編), T 51, no. 2076, pp. 259c–260a (CBETA), accessed September 20, 2025.

《大乘入楞伽經》卷三(唐 • 實叉難陀譯), T 16, no. 672, p. 602a10–22(四種禪總述與各條起首)(CBETA), accessed September 20, 2025.

《楞伽阿跋多羅寶經》卷二(劉宋 • 求那跋陀羅譯), T 16, no. 670, p. 492b(四種禪對讀)(CBETA), accessed September 20, 2025.

《大乘入楞伽經》卷一(劉宋 • 求那跋陀羅譯), T 16, no. 670, pp. 484c–485a (CBETA), accessed September 25, 2025.

《禪行法想經》(傳安世高, 後漢), T 15, no. 605, p. 181b23–26 (CBETA), accessed September 20, 2025.

Robert E. Buswell Jr. and Donald S. Lopez Jr., eds., The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, s.v. “śrāvaka.”

Ibid., s.v. “pratyekabuddha.”

《大乘入楞伽經》, T 16, no. 670, p. 492b18–23(自證聖智三種樂)(CBETA), accessed September 20, 2025.

《歷代法寶記》卷一, T 51, no. 2075, p. 179c: 「我此禪宗,別於餘教。」(CBETA), accessed September 25, 2025.

《續高僧傳》卷三十, T 50, no. 2060, p. 650a(神秀受武后賜號「大通禪師」等記載)(CBETA), accessed September 25, 2025.

《六祖大師法寶壇經》, T 48, no. 2008, p. 353b18–22: 「外於一切善惡境界,心不動,名為『坐』;內見自性不動,名為『禪』。」(CBETA), accessed September 23, 2025.

Ibid., p. 353b22–25: 「外離相為禪;內不亂為定。」(CBETA), accessed September 23, 2025; Robert E. Buswell Jr. and Donald S. Lopez Jr., The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, s.vv. “ding,” “samādhi.”

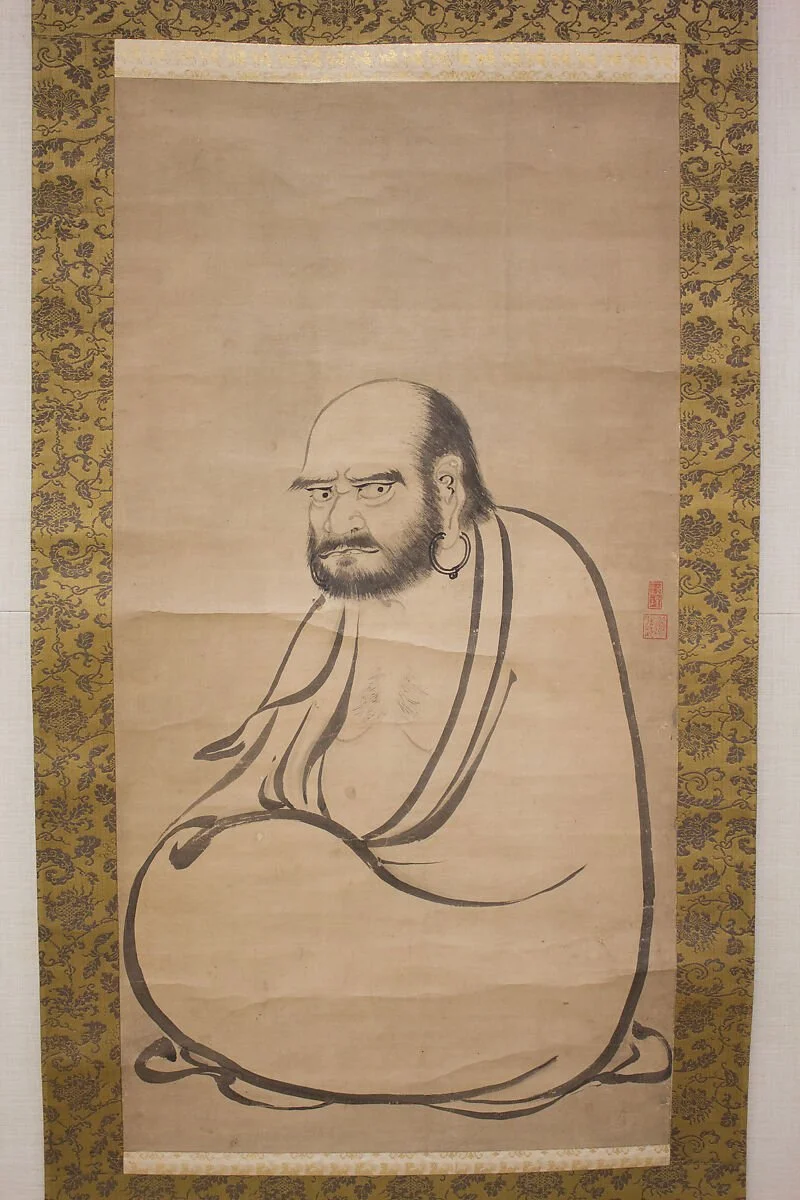

“Bodhidharma (Daruma) by Kano Sanraku (17th century hanging scroll, ink on paper) — a public domain scroll illustrating the Zen ancestor who brought the dhyāna tradition to China.”