PART 5 | The Four Statements of Zen

Beyond Words, Beyond Teaching

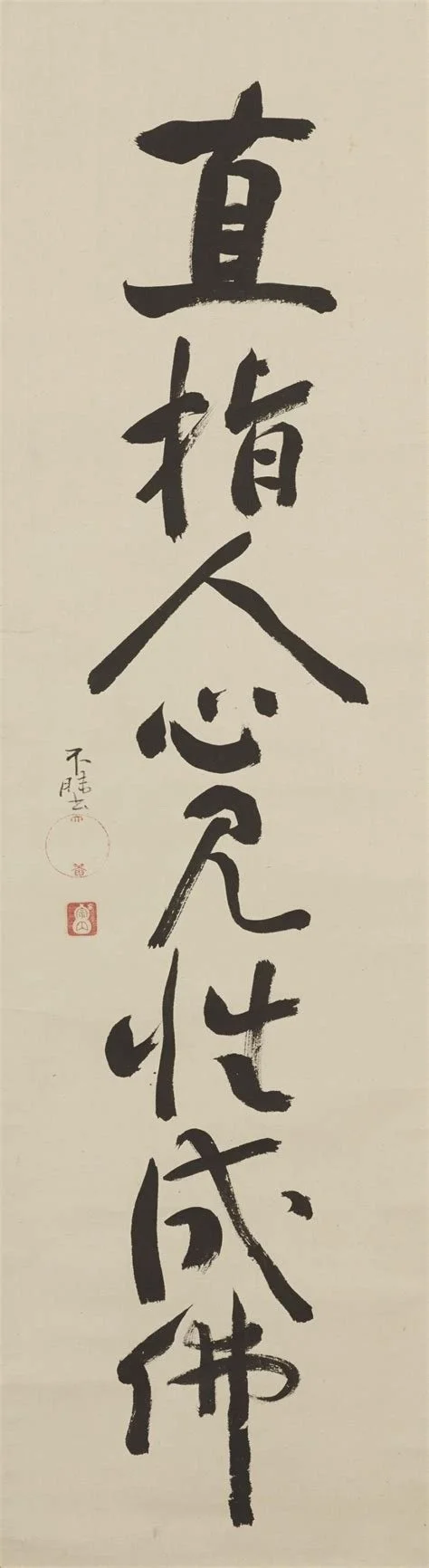

“Directly pointing to the mind-heart.”

Introduction

Few phrases encapsulate the spirit of Zen as succinctly and powerfully as the so-called "Four Statements of Zen." Often attributed to Bodhidharma, the semi-legendary founder of Chan (Zen) Buddhism in China, these four lines are not doctrinal propositions, nor are they philosophical claims. They are best understood as methodological principles: a set of gestures pointing toward a direct experience of mind that lies beyond conceptual thought, scriptural study, or ritual formulation.

Despite their fame in modern Zen circles, the Four Statements are not found in the earliest texts associated with Bodhidharma. Their precise origin, function, and phrasing are all products of historical evolution, shaped by centuries of reflection on what makes Zen distinct. This post aims to examine what these statements are, where they come from, how they have been translated here, and what they mean for contemporary Zen practice.

What Are the Four Statements?

The Four Statements, in their classical Chinese form, read:

不立文字,教外别傳,直指人心,見性成佛。

Not based upon written word.

Separate transmission outside teaching.

Directly pointing to the mind-heart.

See nature become Buddha.

They are often cited as a summary of Zen's essential approach to awakening. Below is a character-by-character breakdown, followed by a refined English rendering for each line. These translations preserve the grammatical minimalism of the original while avoiding the insertion of any subject or interpretive agent that is not present in the text.

Literal Breakdown & Refined Rendering

不立文字 (Bù lì wénzì)

不 — not

立 — establish / base upon

文字 — written characters / script

Literal: “Not establish written characters.”

Refined: “Not based upon written word.”

教外别傳 (Jiào wài bié chuán)

教 — teaching / doctrine

外 — outside

别 — separate / distinct

傳 — transmission / pass on

Literal: “Separate transmission outside teaching.”

Refined: “Separate transmission outside teaching.”

直指人心 (Zhí zhǐ rén xīn)

直 — directly

指 — point / indicate

人 — person / human

心 — mind-heart

Literal: “Directly point person mind-heart.”

Refined: “Directly pointing to the mind-heart.”

Here, ‘person’ (人) refers to the mind from the perspective of the experiencer.

見性成佛 (Jiàn xìng chéng fó)

見 — see / perceive

性 — nature / essence

成 — become / accomplish

佛 — Buddha

Literal: “See nature become Buddha.”

Refined: “See nature become Buddha.”

Where Did They Come From?

Although commonly attributed to Bodhidharma, there is no record of these four lines appearing in any text associated with him during his lifetime or the generations immediately following. They do not appear in early records such as the Two Entrances and Four Practices (入道二門)—one of the few texts linked to Bodhidharma that survives from the early Tang period.

The first complete appearance of the Four Statements as a set occurs in the Wudeng Huiyuan (《五燈會元》), or Compendium of the Five Lamps, compiled by the Chan monk Puji (僥頌) sometime between 1240 and 1253 CE.¹ This massive text was part of the Song dynasty effort to consolidate the lineage and teachings of the Chan tradition into a structured, authoritative record. The Four Statements appear there as a retrospective characterization of Zen's transmission lineage and method.

Although the statements are presented without commentary, their placement within the Wudeng Huiyuan suggests that they were already widely accepted as emblematic of the Chan tradition by the mid-13th century.

Are They Doctrine?

The Four Statements are not doctrinal in the way that formal belief systems or structured philosophies often are. They do not attempt to explain the nature of reality or lay out a systematic path to truth. Instead, they function as pointers—concise expressions of Zen’s direct, experiential approach to awakening.

Each line turns the practitioner away from abstract concepts and toward immediate experience. In this way, they function more like koans or Zen sayings—lessons to be realized through direct experience.

Why Translate Them This Way?

The translation choices here are governed by two commitments: linguistic precision and experiential non-duality. Wherever possible, the translations avoid introducing a subject unless one is clearly stated in the Chinese text. This respects the subjectless grammar of classical Chinese, which in Zen often functions as a mirror of subjectless awareness.

For example, the phrase “Directly pointing to the mind-heart” is closer to the original than alternatives like “pointing to your mind” or “pointing to the human mind,” both of which imply a division between seer and seen. The accompanying note clarifies that the word ‘person’ (人) should be understood as the perspectival appearance of mind, not as an isolated individual or ego.

Similarly, terms like “written word” (for 文字) and “seeing nature” (for 見性) are chosen for their clarity and restraint, avoiding interpretive insertions like “true nature,” which carry metaphysical weight that is not present in the original characters.

Why They Still Matter

While the Four Statements are historical summaries, they are not Zen doctrine. Instead, they are useful reminders. In a time of abundant discourse and digital information, they speak with cutting simplicity.

Do not lean on books. Truth is not found in the words themselves, but in the direct experience of the mind-heart that they point to. Look into your mind, see true nature, and become Buddha.

As my teacher, Great Zen Master Chang Sik Kim, often said: “To attain enlightenment, you must see your own mind.”

These Four Statements are not the destination of Zen; they are the starting point.

Thank you for reading. I hope these explorations support your practice and offer something of value along the way.

In the near future, I plan to explore the origins of Zen in India, more on Bodhidharma, the Four Statements, the origins of Zen in India, the origin of the word Zen (dhyāna) and the teachings of several influential Zen Masters from China. If there are other topics you’d like to see covered in future articles, feel free to send us an email —I’d love to hear from you.

If you find these history blogs valuable and want to see more, consider supporting the Mind Light Way School of Zen, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Your support helps make this research possible and allows us to continue sharing Zen’s rich history with a wider audience.

This article was written by Sebastian Rizzon, Zen Master of the Mind Light Way School of Zen.

Footnotes

Wudeng Huiyuan 五燈會元, compiled by Puji (僥頌) c. 1240–1253 CE. See: Yanagida Seizan, Shoki Zenshu shisho no kenkyu 第一章『水紙師的所言』 (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo, 1971), 421; and Andy Ferguson, Zen's Chinese Heritage: The Masters and Their Teachings (Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications, 2000), 18.

Image: Public domain calligraphy scroll depicting “直指人心 見性成佛”

“Directly pointing to the mind-heart; seeing nature, becoming Buddha”